The Almanack of Naval Ravikant

My personal favourite — selected passages that made me fall in love with the book.

Notes from my reading desk: what I explore, question, and keep.

Notes, essays, and book reviews exploring philosophy, religion, perception, and everyday economics. No pitches or social links—just thinking out loud and refining it over time.

My personal favourite — selected passages that made me fall in love with the book.

History more dramatic than fiction — full chapter-by-chapter note.

Still gathering the best part to put in

Indian context for timeless investing principles.

Currently Reading

Language has limits; experience can exceed words.

If everything shares one source, do food rules stay consistent?

Moral guidance vs deep questions of mind, self, and being.

If I don’t fit any rulebook, what does that say about “creation”?

Perception is narrow — so how “real” is our reality?

Measuring purchasing power by litres per gram.

The Almanack of Naval Ravikant isn’t just a book; it’s a collection of timeless wisdom on wealth, happiness, decision-making, and life philosophy — all distilled from the thoughts of Naval, an entrepreneur and thinker admired worldwide. Unlike typical self-help guides, it doesn’t give you a fixed roadmap. Instead, it teaches you mental models, principles, and ways of thinking that help you design your own path.

This is my personal favourite book. I keep coming back to it because every time I read it, I discover something new, something deeper. Naval’s ideas cut through noise and speak directly to how we can live better, freer, and wiser lives.

For those who may not get the chance to read the entire book, I’ve gathered here some of its most important passages. Even if you just read these, you’ll feel the clarity and power of Naval’s thinking — and you might automatically fall in love with the book, just as I did.

“Set and enforce an aspirational personal hourly rate. If fixing a problem will save less than your hourly rate, ignore it. If outsourcing a task will cost less than your hourly rate, outsource it.”

“The current environment programs the brain, but the clever brain can choose its upcoming environment.”

“I’m not going to be the most successful person on the planet, nor do I want to be. I just want to be the most successful version of myself while working the least hard possible. I want to live in a way that if my life played out 1,000 times, Naval is successful 999 times. He’s not a billionaire, but he does pretty well each time. He may not have nailed life in every regard, but he sets up systems so he’s failed in very few places.”

“Another way of thinking about something is, if you can out-source something or not do something for less than your hourly rate, outsource it or don’t do it. If you can hire someone to do it for less than your hourly rate, hire them. That even includes things like cooking. You may want to eat your healthy home cooked meals, but if you can outsource it, do that instead.”

“It starts becoming so deterministic, it stops being luck. The definition starts fading from luck to destiny. To summarize the fourth type: build your character in a certain way, then your character becomes your destiny.”

“One form of leverage is labor — other humans working for you. It is the oldest form of leverage, and actually not a great one in the modern world. I would argue this is the worst form of leverage that you could possibly use. Managing other people is incredibly messy. It requires tremendous leadership skills. You’re one short hop from a mutiny or getting eaten or torn apart by the mob.

Money is good as a form of leverage. It means every time you make a decision, you multiply it with money. Capital is a trickier form of leverage to use. It’s more modern. It’s the one that people have used to get fabulously wealthy in the last century. It’s probably been the dominant form of leverage in the last century.”

“Basically, if you are making the hard choices right now in what to eat, you’re not eating all the junk food you want, and making the hard choice to work out. So, your life long-term will be easy. You won’t be sick. You won’t be unhealthy. The same is true of values. The same is true of saving up for a rainy day. The same is true of how you approach your relationships. If you make the easy choices right now, your overall life will be a lot harder.”

“People mistakenly believe happiness is just about positive thoughts and positive actions. The more I’ve read, the more I’ve learned, and the more I’ve experienced (because I verify this for myself), every positive thought essentially holds within it a negative thought. It is a contrast to something negative. The Tao Te Ching says this more articulately than I ever could, but it’s all duality and polarity. If I say I’m happy, that means I was sad at some point. If I say he’s attractive, then somebody else is unattractive. Every positive thought even has a seed of a negative thought within it and vice versa, which is why a lot of greatness in life comes out of suffering. You have to view the negative before you can aspire to and appreciate the positive.”

“Least understood, but the most important principle for anyone claiming ‘science’ on their side — falsifiability. If it doesn’t make falsifiable predictions, it’s not science. For you to believe something is true, it should have predictive power, and it must be falsifiable.

I think macroeconomics, because it doesn’t make falsifiable predictions (which is the hallmark of science), has become corrupted. You never have a counterexample when studying the economy. You can never take the US economy and run two different experiments at the same time.”

If You Can’t Decide, The Answer Is No

“If I’m faced with a difficult choice, such as:

→ Should I marry this person?

→ Should I take this job?

→ Should I buy this house?

→ Should I move to this city?

→ Should I go into business with this person?

If you cannot decide, the answer is no. And the reason is, modern society is full of options. There are tons and tons of options. We live on a planet of seven billion people, and we are connected to everybody on the internet. There are hundreds of thousands of careers available to you. There are so many choices.

You’re biologically not built to realize how many choices there are. Historically, we’ve all evolved in tribes of 150 people. When someone comes along, they may be your only option for a partner.

When you choose something, you get locked in for a long time. Starting a business may take ten years. You start a relationship that will be five years or maybe more. You move to a city for ten to twenty years. These are very, very long-lived decisions. It’s very, very important we only say yes when we are pretty certain. You’re never going to be absolutely certain, but you’re going to be very certain.

If you find yourself creating a spreadsheet for a decision with a list of yes’s and no’s, pros and cons, checks and balances, why this is good or bad…forget it. If you cannot decide, the answer is no.”

If you ever watched Game of Thrones and wondered how cruel the writer is, then you should read real history—you will be stunned for sure. The life of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, as described in this biography, proves that truth can be far more dramatic, bloody, and inspiring than fiction. Shivaji’s story is filled with betrayals, daring escapes, epic battles, and impossible dreams—and yet, unlike a fantasy, it shaped the destiny of millions. This book doesn’t glorify him as a myth but shows him as a man who fought against impossible odds and built Swarajya (self-rule) from nothing.

Chapter 1: Raja Shahaji Bhosale

The book begins with Shivaji’s background, focusing on his father, Shahaji Bhosale. Shahaji was a brilliant warrior and a statesman who served different sultanates in a politically fractured Deccan. His shifting loyalties are often judged harshly, but the chapter explains the compulsions of the time—survival in a cut-throat world of Mughal pressure, Adilshahi manipulations, and constant wars. This political landscape directly influenced Shivaji’s early understanding of power and betrayal.

Alongside Shahaji, Jijabai (Shivaji’s mother) emerges as a towering figure. She nurtured young Shivaji with stories of valor, dharma, and justice. The combination of Shahaji’s political wisdom and Jijabai’s moral vision gave Shivaji both practical skills and a sense of higher purpose. By the end of this chapter, we see a child born into turbulence but destined to rebel against it.

Chapter 2: Freedom Above All

Here, Shivaji’s vision of Swarajya takes root. Unlike other rulers of his time who fought for territory or wealth, Shivaji believed in creating a kingdom where people lived with dignity. The chapter highlights his emphasis on protecting commoners, giving justice, and ensuring economic fairness. This was radical in an era when peasants were crushed by taxes and nobility often lived in luxury.

The author also explains how Shivaji absorbed spiritual lessons from saints like Samarth Ramdas, which strengthened his resolve. “Freedom above all” was not just a slogan but the foundation of his political philosophy. It set him apart from all other contemporary rulers and laid the groundwork for his lifelong struggle.

Chapter 3: First Victory

This chapter narrates Shivaji’s first major military success—capturing Torna Fort. It wasn’t just a victory of arms but of vision: Shivaji was a teenager leading a small band of men against established rulers. The success stunned everyone, as it signaled the rise of a new power in the Deccan.

The chapter also describes how this victory boosted the morale of his followers and started attracting more warriors to his side. What makes it remarkable is Shivaji’s use of planning, secrecy, and surprise—tactics that would later define his guerrilla warfare. Torna became the first stone in the foundation of Swarajya.

Chapter 4: Political Turmoil

The book then shifts to the broader stage of 17th-century India. Aurangzeb’s ambitions, Adilshahi decline, and the Portuguese and Siddis controlling the coasts created a complex web of politics. For a young leader like Shivaji, navigating these forces was like walking a tightrope.

This chapter shows how Shivaji learned to play diplomacy as skillfully as he fought wars. He made treaties, broke them when necessary, and always ensured that his small kingdom wasn’t swallowed by bigger predators. It’s a reminder that statecraft was as important as the sword in his rise.

Chapter 5: An Impossible Dream

Calling Swarajya an “impossible dream” was no exaggeration. In this chapter, the author emphasizes how the odds were stacked against Shivaji—tiny resources, a handful of forts, and enemies like the mighty Mughals and Adilshahis. Any rational observer would have dismissed him as a rebel doomed to fail.

Yet, Shivaji refused to accept the limits of his time. The chapter paints him as a dreamer who dared to imagine what others could not. His genius lay in combining vision with relentless action—rallying farmers, training soldiers, and inspiring loyalty with a sense of justice.

Chapter 6: Death of Afzal Khan and Its Aftermath

One of the most dramatic moments in Shivaji’s life unfolds here. Afzal Khan, a giant of a general sent by the Adilshahis, tried to crush Shivaji by deceit. Shivaji, anticipating betrayal, wore armor under his clothes and carried hidden weapons. In the famous meeting, he killed Afzal Khan with his tiger claws, shocking the Deccan world.

The aftermath was equally explosive—Shivaji’s troops quickly captured surrounding forts and territory, multiplying his power. This event made Shivaji a legend, proving his intelligence and courage. But it also ensured that he would never again be underestimated by his enemies.

Chapter 7: Shockwaves Across the Mughal World

The news of Afzal Khan’s death sent ripples across India. The Mughals, who had considered Shivaji a minor rebel, now saw him as a dangerous threat. Aurangzeb began to take him seriously, preparing campaigns to crush him.

The chapter also highlights how Shivaji’s reputation soared among the common people. He became a symbol of resistance, admired not only by Hindus but also by many Muslims who suffered under corrupt governors. His actions gave hope that tyranny could be challenged.

Chapter 8: Cataclysmic Meeting

This chapter deals with Shivaji’s interactions with Aurangzeb and the Mughal court. The clash wasn’t just about power—it was ideological. Aurangzeb represented imperial expansion and religious orthodoxy, while Shivaji stood for self-rule and pluralism.

The tension between the two men culminated in Shivaji’s visit to Agra. What was supposed to be a diplomatic meeting turned into near imprisonment. Shivaji’s pride was insulted, and Aurangzeb underestimated his resilience—setting the stage for a historic escape.

Chapter 9: The Great Escape

Perhaps the most thrilling part of Shivaji’s story, this chapter narrates how he escaped from Agra, where he was virtually a prisoner. Disguised in baskets of sweets and carried past Mughal guards, Shivaji outwitted the empire’s mightiest ruler.

The escape wasn’t just a physical victory—it was psychological. It proved that no fortress or emperor could contain his spirit. The tale of the Agra escape spread like wildfire, elevating Shivaji into a near-mythical figure in the eyes of the masses.

Chapter 10: The Calm Before the Storm

After the Agra episode, Shivaji spent time consolidating his power. The chapter shows how he reorganized administration, built forts, strengthened his navy, and expanded his army. He wasn’t only a warrior but also a planner.

This period also reflects Shivaji’s wisdom: he knew when to fight and when to pause. By building a strong foundation, he ensured that Swarajya wouldn’t collapse even if he fell in battle.

Chapter 11: Becoming Chhatrapati

In 1674, Shivaji was formally crowned as Chhatrapati at Raigad Fort. The coronation was not just a ritual but a statement of sovereignty. For the first time in centuries, a native Indian king declared independence from both foreign invaders and internal tyrants.

The chapter captures the grandeur of the event—holy ceremonies, cheering crowds, and the symbolism of reclaiming dignity for the people. Shivaji became not just a military leader but a legitimate monarch.

Chapter 12: Triumph and Tragedy

This chapter covers the later years of Shivaji’s reign. Victories continued, but so did challenges. Wars with the Mughals, conflicts with local rivals, and betrayals tested his strength. He expanded his kingdom but also faced personal tragedies.

The narrative emphasizes that power always came at a price. Shivaji never stopped fighting, but the endless struggle took its toll. His story reminds us that even great leaders are human, burdened by losses and exhaustion.

Chapter 13: Epilogue

The book ends by reflecting on Shivaji’s death in 1680 and the legacy he left behind. Though he passed away, the Maratha Empire he founded grew stronger and eventually challenged Mughal supremacy across India.

The epilogue highlights Shivaji’s principles: respect for human dignity, fair governance, and visionary leadership. These values made him more than a conqueror—they made him a legend whose relevance continues even today.

Still gathering the best part to put in

It can be described as the Indian version of The Intelligent Investor. While Benjamin Graham’s classic gives timeless principles of investing, Pranjal Kamra makes them relatable for Indian readers by using examples from Indian companies, market conditions, and financial habits. That’s what makes this book unique—rather than abstract Western case studies, it directly addresses the Indian retail investor’s journey.

One of the most striking parts of the book is the mention of the Rule of 70/72/75, which is a quick mathematical shortcut to calculate how long it takes for your investment to double. For example, if the expected return rate is 10%, you divide 72 by 10 and get 7.2 years. This simple rule is extremely powerful because it helps beginners understand the magic of compounding in an easy and practical way.

🌟 Key Strengths of the Book

📑 Structure & Flow

⚖️ Critique

The book is best for beginners and early investors. Experienced investors may find some concepts too basic.

Some examples are simplified, which is good for learning, but advanced readers might crave more depth in financial ratios and valuation methods.

✨ Final Thoughts

Investonomy is one of the most practical starter guides for Indian investors. Where Graham’s Intelligent Investor teaches timeless principles in an American context, Kamra’s book adapts those principles to Indian realities—like market volatility, cultural attitudes towards gold and real estate, and the importance of patience in a developing economy.

The biggest takeaway is that wealth creation is not about chasing quick profits, but about time, patience, discipline, and compounding. If you are an Indian investor just starting out, this book will give you both confidence and direction.

An Introduction to Indian Philosophy — Satishchandra Chatterjee & D.M. Datta

This classic text serves as a gateway into the vast landscape of Indian philosophical traditions. It introduces readers to schools like Nyāya, Sāṃkhya, Vedānta, Mīmāṃsā, Buddhism, and Jainism, explaining their key ideas about existence, knowledge, and liberation.

Right now, I’m exploring this book as my currently reading choice. It’s not a light read, but it’s rewarding — every page deepens my understanding of how Indian thinkers approached truth, reality, and the human condition.

“So when we read or listen about divine characters or teachers like buddha, krishna, mohammad or jesus I wonder why they didn’t explained the truth in very simple words but today i got my answer why bcz it might be something beyond our experience and limited by our language as well for instance if there is an alienated group of monkeys living in jungle and one monkey saw a dinosaur one day how he will explain it to the group if his language doesn’t allow it to do so another example is suppose i read so much and from somewhere I found that god lives on mars and i go to mars see the god which is ‘egg’ shaped then explain it to my friends but here is the catch suppose egg never existed on earth how will i explain that shape to them if i will say it is combination of one big and one small sphere then they will get it as avacado which is wrong again so what i think is truth cannot be known it can only be experienced”

Today, I had a realization while thinking about divine teachers like Buddha, Krishna, Muhammad, or Jesus. I often used to wonder—if they truly knew the ultimate truth, why didn’t they just explain it in simple, direct words? Why leave room for interpretations, metaphors, or ambiguity?

But now, I feel I may have found the answer. Perhaps the truth they spoke of is something beyond normal human experience—something our limited language simply cannot capture.

To make sense of this, I imagined a group of monkeys living deep in the jungle. One day, one monkey sees a dinosaur. But his language has no word for it—no concept, no reference. So even if he wants to describe it, how can he? His language doesn’t allow it.

Another example came to my mind: suppose I somehow discover that God lives on Mars, and when I reach there, I find that God is in the shape of an “egg.” Now, I come back to Earth and want to share this discovery. But imagine—what if eggs never existed on Earth? If I say God is a combination of one big and one small sphere, people might picture an avocado. That would be inaccurate. So how can I ever convey what I truly saw?

From this, I conclude that the ultimate truth cannot be fully known through words. It cannot be explained—it can only be experienced. Language has its boundaries, and truth, perhaps, lies beyond them.

“So when people say no I don’t eat beef or i don’t eat pork because of my religious beliefs so we can assume that, actually we can surely say that they are believers of God as creator cause every religion except ‘Buddhism’ and ‘Jainism’ believe in God as a creator so what I think is if they believe everything is created by god it means everything comes from same basic substance so if you don’t eat beef and pork but can eat chicken and lamb then eventually you are distinguishing same thing in different forms if everything comes from same substance then how does it matter to not eat something and eat rest of the thing!??”

Today, I reflected on a common statement people often make: “I don’t eat beef” or “I don’t eat pork” because of their religious beliefs. From this, we can safely assume—or rather, surely say—that they are believers in the idea of God as the creator. This is because almost every religion that sets such dietary rules, except for Buddhism and Jainism, fundamentally believes in a God who created everything.

Thinking deeper, if they believe everything is created by God, then it logically follows that everything comes from the same basic substance. If that is the case, then refusing to eat beef or pork but still eating chicken or lamb seems inconsistent. Essentially, they are distinguishing between the same basic creation, just appearing in different forms.

If all life and all matter originate from the same divine source, how can one part be considered acceptable to consume while another is forbidden? If everything shares the same essence, the separation between what is pure and what is impure, or what can be eaten and what cannot, appears artificial and contradictory.

This thought leads me to question the deeper logic behind such dietary restrictions when viewed through the lens of a belief in a single creator and a single origin for all beings.

“When you read about this monotheistic religions you will fill like you’re reading about fictional tale bcz they only talk about morality, justice, love, sex in short ways to live your life they don’t have any deep philosophies like they don’t talk about soul or existence of being they just say we are creation that’s it no any focus on mind body or monism dualism nothing,,,unlike them all eastern philosophies have this ideas about soul and existentialism that is why there is no concept of renunciation in all monotheistic religions if you really want to explore western philosophies then the way is reading original philosophers like Kant, Descartes, and all….”

Today, I found myself contemplating the differences between monotheistic religions and other philosophical traditions, particularly those from the East. When I read about monotheistic religions like Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, it often feels as if I’m reading a simplified narrative focused primarily on morality, justice, love, sex, and general guidelines for how to live a righteous life. Their teachings tend to revolve around prescriptive rules and ethical principles rather than deeper explorations of existence, consciousness, or the nature of being.

What strikes me the most is their limited scope when it comes to philosophical concepts. They emphasize the idea of creation—asserting that we are created beings with a specific purpose defined by a divine entity. Yet, they don’t seem to delve into profound questions about the nature of existence, the mind, or the relationship between body and soul. Concepts like monism, dualism, or even the exploration of consciousness are largely absent. Instead, their focus is more on establishing a moral framework than examining the underlying essence of life or being.

In contrast, Eastern philosophies, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Confucianism, and Taoism, offer much more intricate discussions about the soul, consciousness, and existential questions. They address ideas like Atman (the soul), Brahman (the ultimate reality), Maya (illusion), karma, and moksha (liberation). These traditions also grapple with complex philosophical inquiries about the self, the nature of reality, and the relationship between mind and body. The concept of renunciation—leaving behind worldly desires to seek higher truth or enlightenment—is central to many of these philosophies, reflecting their dedication to exploring deeper existential questions.

Interestingly, monotheistic religions don’t seem to emphasize renunciation or self-transcendence in the same way. They are more focused on guiding people to live moral and ethical lives within society rather than encouraging them to transcend worldly existence altogether.

If I want to explore profound questions about existence, consciousness, and the nature of being, I find myself drawn more toward philosophical traditions rather than religious doctrines. In the West, the closest approach to such deep inquiry comes not from religion, but from philosophers like Kant, Descartes, Nietzsche, and others who dared to question the foundations of knowledge, reality, and consciousness.

It feels as if the religious framework of monotheistic traditions is inherently limited in addressing the deeper philosophical inquiries that interest me. To truly understand and explore these concepts, I have to step outside of religious doctrines and dive into the works of original philosophers who dared to ask fundamental questions about existence itself.

“My idea or learning of today is if according to hindu scripture I should not eat non veg but i do i am not Hindu and align with it according to islam same about alcohol I eat chicken and drink alcohol according Christianity do not go church every sunday so if any god created me why he created me like this he should create me with an inbuilt livelyhood that aligns with that religion so I believe i am not being created”

Today, I found myself questioning the relationship between religious teachings and my own actions. According to Hindu scriptures, eating non-vegetarian food is prohibited, yet I eat it. Similarly, Islam strictly forbids the consumption of alcohol, but I drink alcohol. Christianity emphasizes the importance of attending church, particularly on Sundays, but I do not follow this practice either.

This inconsistency between religious teachings and my actions leads me to a deeper question: If any God truly created me, then why was I not created with an inherent nature that aligns with the principles of that religion? If I was meant to follow these guidelines, wouldn’t it be natural for me to do so without conflict or hesitation?

If a divine creator intended for me to adhere strictly to a specific set of rules, then shouldn’t those rules have been embedded within me as instinctive traits? Instead, I find myself engaging in actions that are considered wrong or forbidden by various religious standards. This suggests a fundamental disconnect between what religious doctrines expect from me and how I naturally behave.

The very fact that I am capable of living in ways that contradict these teachings makes me question whether I was created by a divine being with a predetermined purpose or nature. If I were created to follow a particular religion’s teachings, then why is it that my lifestyle and choices diverge so significantly from those expectations?

It feels as though I exist independently of these religious frameworks, as if my thoughts, desires, and actions are shaped by something other than divine design. This thought challenges the idea that I was created with an inbuilt nature that aligns with any specific religion.

This realization leaves me questioning the concept of divine creation itself. If I were truly created by a god with a purpose or set of guidelines to follow, then why is my natural inclination so often at odds with those teachings?

The more I consider this, the more it feels as if my existence and actions are not the result of divine creation but rather something else entirely.

“What is running in my mind now is when I read about the four ways of gathering knowledge in nyaya philosophy (or something else correct it) one of which is perception so what i think is what ever we see is not true cause our eyes can see only some percentage of light we can’t even see infrareds and ultraviolet and what ever we see is for comfort for our vision otherwise snake has different vision, tiger has, so cow has there is no proof of us having perfect and real vision.”

What’s been running through my mind today is something I read about in Indian philosophy—specifically from the NYAYA school. It discusses the four valid means of knowledge, one of which is perception (pratyaksha).

But this got me thinking: can we really trust perception as a reliable way of knowing the truth? Whatever we see with our eyes is already limited. Human vision can only detect a narrow range of light on the electromagnetic spectrum. We cannot see infrared or ultraviolet rays. So much exists beyond our visible range, yet we act as if what we see is the complete reality.

Moreover, what we perceive is not even consistent across living beings. A snake sees through infrared sensing, a tiger has night vision, and a cow likely sees things very differently from us. Each species has a different range of perception shaped by its own biological needs.

So where is the proof that our human vision reflects perfect or ultimate reality? What appears “normal” to us may be completely different for another creature. This makes me question whether what we see can ever be called the absolute truth—or whether it’s just a version of reality shaped for our survival and comfort.

If perception is one of the main ways we claim to know the world, and yet it is so limited and subjective, then how much of what we call “reality” is just a filtered illusion?

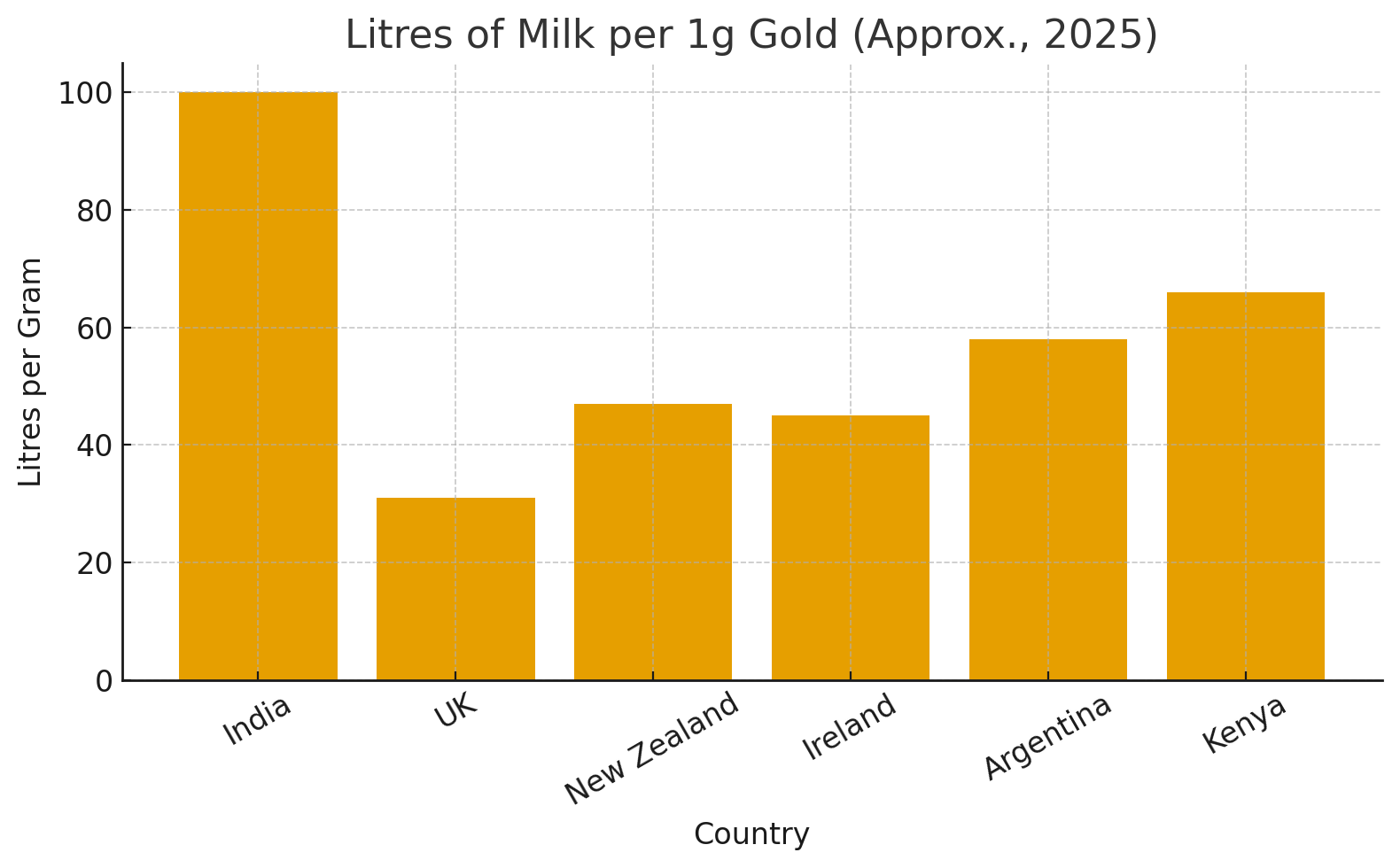

Conventional inflation statistics often feel abstract and disconnected from everyday life. To make the idea more tangible, I explored a simple question: How many litres of milk can 1 gram of gold buy? This approach connects a global standard of value (gold) with a universal daily necessity (milk), turning inflation into something measurable in everyday terms.

Litres per gram = (Gold price per gram) / (Milk price per litre)The first test was between the United Kingdom and India. In the UK, 1 gram of gold bought far fewer litres of milk compared to India. This difference highlighted how self-reliance in dairy directly affects affordability. India, as the world’s largest milk producer, benefits from large-scale local production, while the UK faces higher costs linked to imports and supply chains.

Building on this, the comparison extended to other self-sufficient dairy nations such as New Zealand, Ireland, Argentina, and Kenya. These countries were chosen because their strong domestic production provides a more reliable benchmark for the gold ⇄ milk ratio.

| Country | 1g Gold Price (local) | Milk Price (per litre) | Litres per Gram (approx.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | ₹6,000 | ₹60 | 100 | Largest producer, high self-reliance |

| UK | £50 | £1.60 | ~31 | Higher costs, import influence |

| New Zealand | NZ$95 | NZ$2.00 | ~47 | Strong exporter |

| Ireland | €55 | €1.20 | ~45 | Strong EU dairy |

| Argentina | ARS 70,000 | ARS 1,200 | ~58 | Volatile economy |

| Kenya | KSh 8,000 | KSh 120 | ~66 | Largely self-sufficient |

The litres-per-gram measure shows that countries with strong domestic dairy sectors — such as India, New Zealand, and Ireland — allow gold to stretch further, providing more litres per gram. By contrast, countries reliant on imports or with higher production costs, such as the UK, show a lower ratio.

This highlights that inflation is not experienced equally across nations. A standard inflation rate does not capture how affordability differs when measured against everyday essentials. The gold ⇄ milk ratio exposes the impact of self-reliance, production costs, and local market conditions.

The Gold ⇄ Milk yardstick is not meant to replace official inflation statistics, but it adds a practical, relatable perspective. By grounding inflation in something people consume daily, it bridges abstract economics with lived reality. More importantly, it demonstrates that affordability is shaped not just by prices but by what a country can reliably produce for itself.